“Cold Ecstasy is the ultimate memory rush. It’s the album I’ve always wanted to make“

Cold Ecstasy is the latest album from 36 – the ambient and experimental electronic music project of UK artist Dennis Huddleston. An homage to the happier, more emotionally-charged aspects of the UK hardcore and rave scene, it is a truly beautiful body of work, playing with themes of memory and deeply rooted in nostalgia: something with which I have an arguably unhealthily obsession.

I love Cold Ecstasy, so was delighted that Dennis agreed to answer some questions about his inspirations and approaches to its creation.

For the majority of the 00s and 2010s – and arguably even in its 90s heyday – trance and the happier aspects of hardcore were pretty much written off as unserious and not worthy of respect. Why do you think that is?

People are too serious, perhaps? Look, I get it. There were some absolutely dreadful happy hardcore tunes. Things got pretty stupid after 1997. But UK hardcore has always had this duality, right from the get-go. For every classic tune like Ellis Dee’s “Free The Feeling” we also got gimmicky trash like “Sesame’s Treet”. Happy hardcore just took things to the extreme, since the bad stuff was really, really bad. It was an easy target, I found it hilarious how Sharkey was a key part of hardcore’s downfall with much-maligned tunes like “Toytown”, yet he was also instrumental in pushing the Freeform sound years later, which gave us so many great tracks. As I say, such is the duality of man!

Of course, it’s a phenomenon which isn’t exclusive to hardcore. Every genre has good and bad tunes. It encourages you to dig deeper to find the stuff that shines brightest. Believe me, there’s plenty of classic happy hardcore tracks, if you give it a chance. I wouldn’t have listened if they weren’t there.

Like you I wasn’t quite old enough for the early 90s raves, but also collected tape packs from the obsessively. Why do you think you were drawn to these rather than, say, more traditional rock or pop music from that era?

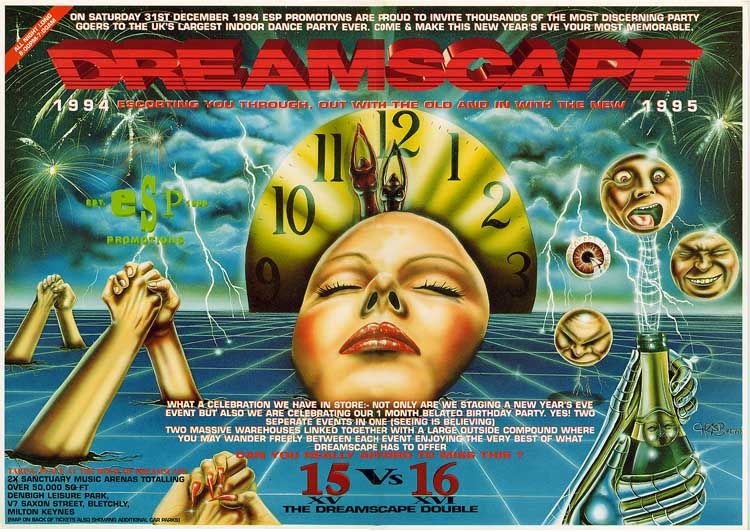

It was the music my sister was listening to at the time, so it fell naturally into my lap too. Obviously I heard all the mainstream pop stuff on the radio, but I was about 10 years old and was beginning to find my own musical personality. I liked how illicit it all felt. The tunes were loaded with drug references and sampled films like The Terminator. It felt very naughty. Plus the artwork used on the posters were so futuristic looking. The Dreamscape and Ark flyers in particular had such a cool aesthetic. The Cold Ecstasy artwork pays homage to them.

I remember a local record store in my home town where I used to get the tape packs from. The first few times I went in, they looked at me funny and wondered what the hell I was doing there. But I just loved the music and eventually began to win them round. There were so many great tunes in the early 90s and by the time happy hardcore got popular in the mid 90s, I just kept going with it. I love all underground UK music. Jungle and happy hardcore may have split apart, but there were vibes to be had with both. It seemed silly to me to abandon one for the other, so I didn’t and bought everything I could afford, across both genres.

A notable moment that things started to change for me was a mix Bicep made back in 2016 for Radio 1 where they played a load of trance records but massively pitched down, after which it started being credible to like this kind of music again. Do you think it takes prominent artists to help change the overall perception of a genre?

At the time, I didn’t really know much about Trance, as it wasn’t really my thing. It felt more like a mainland Europe genre, whereas hardcore/jungle were home-grown UK sounds, more relevant to me. When I was older, I dug deeper into the history of electronic music and where it came from. Tracks like “First Power” by “Revelation” really hit me. That sort of prototype Trance sound, but still rooted in Techno and House. It was actually through hardcore that I discovered more tunes that were in the Trance sphere, albeit on the harder side. Tracks like “Listen Carefully” by “R. Wagner”. Absolute monster of a tune. Also, a friend of mine was really into the stuff on the Platipus label, which I began to enjoy too. Very smooth, beautiful music. It’s still not really a genre I listen to much, but I appreciate the tunes that did make an impact on me.

As for bigger artists using the tunes in new ways, I think it’s all good, as long as they treat the genre with respect and do it from a place of love, wanting to share past sounds with future ears. John Peel did that with hardcore. BICEP are great and have supported my music in their live sets, so they get the thumbs up from me.

Part of the appeal of Cold Ecstasy is the strong sense of nostalgia it evokes. Do you consider yourself someone prone to nostalgia, and if so, how do you ensure the music you produce stays relevant to the present day?

Yes, hopelessly so. I’m 40 now, which means I’ve stockpiled plenty of emotional baggage, regrets, all that fun stuff! Music is the best outlet for it. Cold Ecstasy is probably the most personal album I’ve made, in the sense that it explicitly catalogues my past and re-interprets it to where I am now. It’s the ultimate memory rush. It’s the album I’ve always wanted to make, but it required half a lifetime do it justice, both technically and emotionally.

Even so, I didn’t want to simply regurgitate the past. People tried that with that “nu rave” stuff in the mid 00s, which always felt like a hollow pastiche compared to the original 90s hardcore productions. The sounds were there, but something was missing. You can’t simply just take music from past and bring it back into the present, because time and place are critical to what makes an era of music so special to begin with. With Cold Ecstasy, I was very conscious of this fact and I treated my influences with reverence and respect. But I needed to bring something new to the table, rather than just let it become an exercise in nostalgia. I think it’s a unique record, which is respectful of the past, but is very much focused on the here and now.

You had a huge wealth of music to choose from in terms of sampling, and I’m sure people will recognise a few of them. Were there any tracks in particular you immediately thought of pillaging when you first conceived the album?

For clarity, Cold Ecstasy is about 99% original production. In fact, only the vocals were sampled, because these were essential to the concept of the album. It was important for me to use these vocals in a way that was different from their original intention. Most of the vocals from this era were unashamedly hyper-positive, which is great and a big part of why I love them. We all enjoy a good hands in the air anthem. But when I sampled them and used them in the context of my music, the vibe changed completely. There’s this sadness to them now. A kind of yearning, like the halcyon days of old have long since passed and the future is more uncertain. For most of my listeners, who likely have zero-knowledge about UK hardcore, they won’t recognise any of these vocals. Even old hardcore heads may struggle with some of them, due to the way I processed them and how disconnected they are from the original intent.

I used Melodyne a lot during this album. I sampled bits of each vocal, cut them up, re-arranged them, and often changed the melody itself to best suit the mood I wanted. While most vox were sourced from old hardcore records, not all of them were. I tried not to be too precious with things. The goal was to make a coherent sounding album, which took the memories I have of the mid-90s, redshifted through the passage of time, relevant to the people of today.

If art is a reflection of the times in which it was made, why do you think there’s more of a trend towards introspection in music, arguably more now than ever before, not just in electronic music, but across the board?

The youth of today have no choice but to self-reflect because they’re living in a world which is so utterly rigged against them. They shouldn’t have to worry about adult stuff, but that looming sense of hopelessness bleeds into every aspect of their lives, so they’re forced to grow up sooner than they should. It’s brutal out there and things are only getting harder. It’s no surprise that music acts as a sort of therapy to deal with all the shit. Music won’t save us, but it does make the grind of life a little less punishing.

How much do you pay attention to what contemporaries of yours are producing, and to what extent – if at all – are you inspired by other musicians?

I spend most of my time working on my own stuff, which leaves increasingly little time to listen to anyone else’s. I often lament the fact that learning how to produce my own music effectively killed the joy I used to get from listening to other artists. I saw behind the curtain and much of the magic was gone. In terms of ambient music, I rarely if ever listen to music made by my contemporaries. I have nothing but respect for them because believe me, I understand the struggle involved. But most of my influences are from older music I grew up listening to, outside this genre. Any free time my ears have are usually spent listening to them instead, because that’s where my heart still is.

It’s probably a big reason why I managed to make an impact in this particular niche, because my musical world-view is quite different to most producers in this genre. I don’t even think I make ambient music. It’s just 36 stuff to me. I leave the pigeon holing to everyone else and have no issues with it, because quite frankly, I don’t really care what other people think of my music. I make it for myself. If other people enjoy it, then that makes me very happy, but even if they all hated it, I wouldn’t stop. I think you have to be utterly selfish when making art, otherwise you’re just an entertainer or worse… A “content creator”.

You’ve described Cold Ecstasy as a companion piece of sorts with 2021’s Weaponised Serenity – are there any other niches or aspects of 90s music you’d like to explore with future projects?

I don’t think so, since I don’t have the same level of connection with any other genres. Weaponised Serenity was my deconstruction of jungle and this is my deconstruction of happy hardcore. I feel confident that nobody else could have made them in quite the same way, since they’re tied so closely to my own unique musical upbringing. Believe me, I’m aware that the amount of listeners who love both ambient and hardcore can probably be counted on one hand, but for those few people, these albums are for you! I really hope they can feel the passion and love I poured into them. As for everyone else, I encourage them to listen with an open mind. Perhaps these albums will act as a bridge between worlds, inspiring them to discover a different, but similarly beautiful genre of music, outside their usual focus.